on electronic participation, collective moderation, and voting systems Issue 7

2022-09-24

The Temporal Dimension in the Analysis of Liquid Democracy Delegation Graphs

Abstract

In ongoing discussions on liquid democracy, we sometimes find arguments which appear to be based on the isolated examination of delegation graphs for a single decision as the underlying model.

We believe that a comprehensive analysis of the functionality and the impact of liquid democracy requires a broader view, namely adding a temporal dimension to delegation models.

It may be necessary to consider that the full potential of liquid democracy cannot be unleashed in singular votings but ongoing governance executed by multiple votings. Furthermore, it may also be necessary to consider that—at least in practical applications—votings are regularly preceded by a deliberation phase, which also could make use of liquid democracy for debate empowerment.

Based on these assumptions, both aspects, multiple votings and a preceding deliberation phase, require an analysis of effects occurring over the time. This includes participants adapting their own behavior in respect to setting, changing, and removing delegations and their own participation based on observations of the actions or non-actions of their (direct and indirect) delegates as well as the actions of other participants (who are potential delegates).

We show that the importance of delegation chain endpoints may be rigorously overestimated because they are based on the wrong assumption that a delegation indicates non-participation. Furthermore, we will show that circular delegations can be seen as compound delegation chain endpoints which do not promote a decline of votes.

Introduction

Over the years, we noticed discussions on several topics related to liquid democracy, especially delegation graphs, which have one common denomination: They seem to be based on the isolated examination of delegation graphs for a single decision as the underlying model. We would like to mention the following papers as an example.

Grammateia Kotsialou and Luke Riley notice that if a delegate abstains, the assigned voting rights are left unused. The authors are searching for solutions to minimize the number of unused delegations. [1]

Palash Dey, Arnab Maiti, and Amatya Sharma see problems with delegates receiving a large number of incoming delegations and propose solutions which would limit the number of delegations per delegate. In the paper, they also take it as a given that cycles need to be resolved. [2]

While all these papers, as well as conversations we had, discuss exciting questions and are of mathematical interest, they may not consider the effects of behavioral change of participants based on their observations of the actions and non-actions of other participants over the time. Therefore, we believe that they do not fully reflect the implications of the practical application of liquid democracy.

Assumptions

Liquid democracy for the self-organization of a large scale group thrives if it is continuously applied to a great number of decisions from a wide range of areas. This is where liquid democracy's dynamic division of labor can unfold its potential.

Social choice theory suggests that the ability to determine the voting options is equally as important as being able to vote. [3] A structured deliberation (using liquid democracy as a debate empowerment) can generate the set of answers, in other words: identify the viable voting options by pondering pros and cons as well as consider alternatives. This also contributes to informed decision making.

In a governance system with a continuous stream of decisions, we expect that participants observe the actions (and even non-actions) of other participants, in particular the activities of their (direct and indirect) delegates as well as the activities of other participants, who they consider as delegates. Based on their observations, we expect participants to adapt their own behavior in respect to setting, changing, and removing delegations and their own participation. Based on the track records of the participants, a network of trust or dynamic scheme of representation proves itself to be a responsible power structure.

The choice is not between delegating and voting

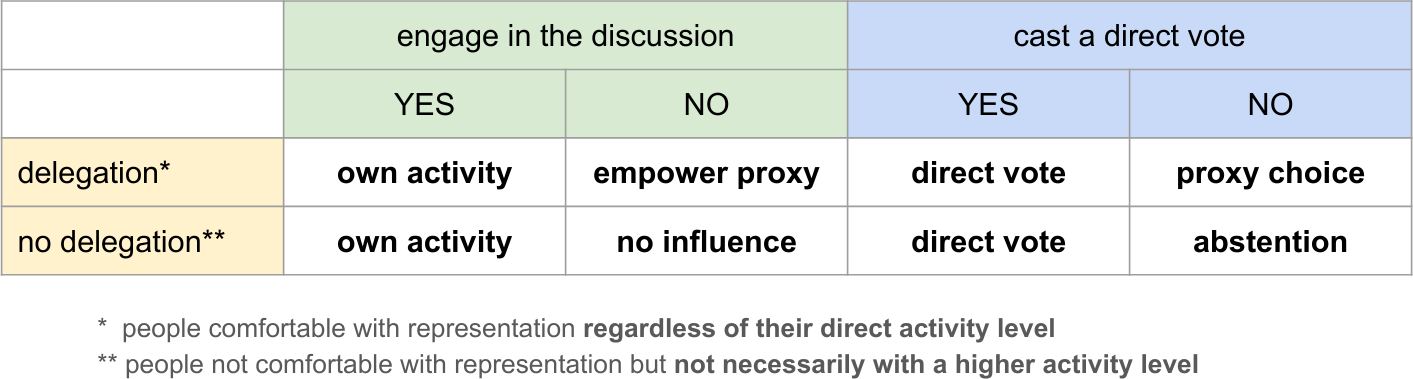

In the discussion, it is often assumed that there is a binary choice between delegating and voting. However, there is an obvious third option: doing nothing.

Looking at practical implementations, it can be seen that there are even more options for the course of action which fundamentally influence the validity of delegation models. For instance, in the LiquidFeedback process [4], we find the following options:

Participants can opt for representation by setting defaults for an organizational unit, override them by default delegations for subject areas, and even override them by issue delegations. They can also opt against representation. In either case, changes of these preferences and direct participation is always possible.

This way, participants contribute to the adjustment of a dynamic scheme of representation, e.g. by responding to non-action or unexpected actions of delegates. Such effects can only be analyzed if the system is observed over time.

The importance of endpoints may be overestimated

By endpoints we mean the end of a delegation chain, i.e. agents with incoming but without outgoing delegations. These endpoints are often focused upon as being especially important assuming they are the agents which will actually cast votes. However, in practical terms there is no reason to believe that.

There is no guarantee that Chris (the current “endpoint”) casts a vote. Likewise, Bob can independently cast a vote which would make him the “endpoint” and turn Chris into a solo-voter.

The delegation graph contains no information on whether or not a participant will act or vote directly. Recipients of multiple delegations are typically active participants. This is true for many endpoints but also for many nodes along the way.

The delegation graph is deconstructed by activity or voting breaking up delegation chains. Higher participation, e.g. in important decisions, increases the deconstruction effect resulting in shorter actual delegation chains.

We expect the network to adjust to undesired behavior of a delegate and do not see a need for algorithmic intervention automatically “rescuing” unused votes. As an unintended side effect of such an algorithmic intervention, the network might even lose its ability to learn.

Compound endpoints

If delegation chains “terminate” in a cycle, this cycle can be seen as a “compound endpoint” where every participant in the cycle can trigger the full voting weight of multiple delegation chains leading to the “compound endpoint”. By doing so, the cycle is automatically resolved.

We argue that delegation cycles are just another kind of endpoint and either remain irrelevant, or—thanks to the suspension of outgoing delegations upon activity—are automatically resolved. It has also been observed that some active participants intentionally create cycles as an additional fallback.

Conclusion

Even if we only looked at the specific implementation of liquid democracy in LiquidFeedback, we were able to show that if the temporal dimension is ignored when considering delegation models, the results of the observation cannot be applied to all practical implementations of liquid democracy. Furthermore, we believe that the effects that occur through observation and adaptation over time are an essential prerequisite for a comprehensive understanding of liquid democracy.