on electronic participation, collective moderation, and voting systems Issue 4

2015-07-28

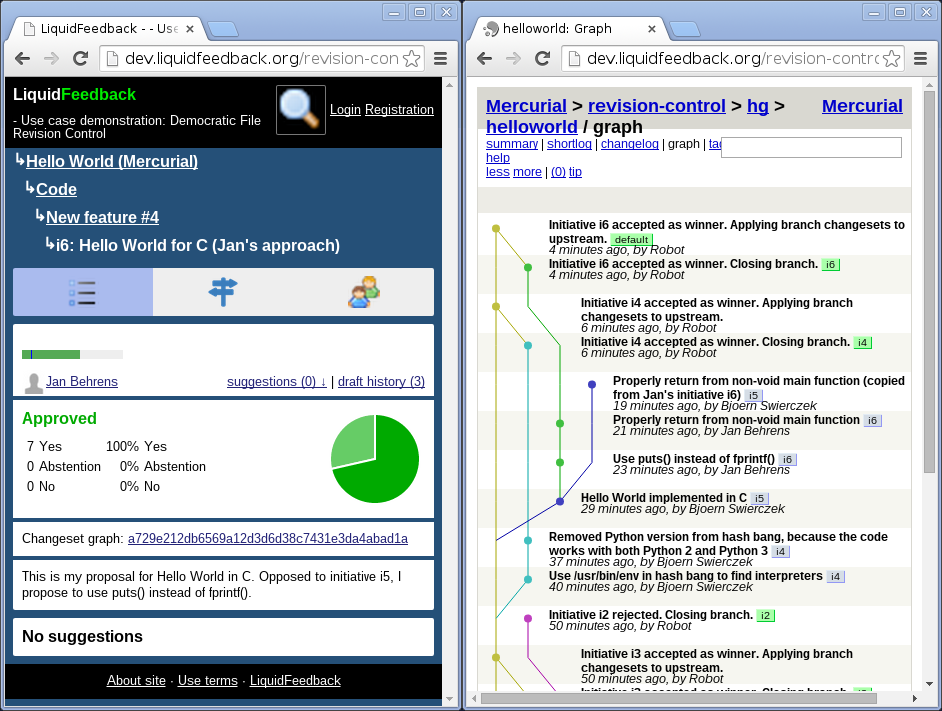

Democratic File Revision Control with LiquidFeedback

I. Abstract

In this paper, it is shown how a project team can democratically decide on incorporating changes of files held in a repository managed by a revision control system by extending LiquidFeedback and its proposition development and decision making process.

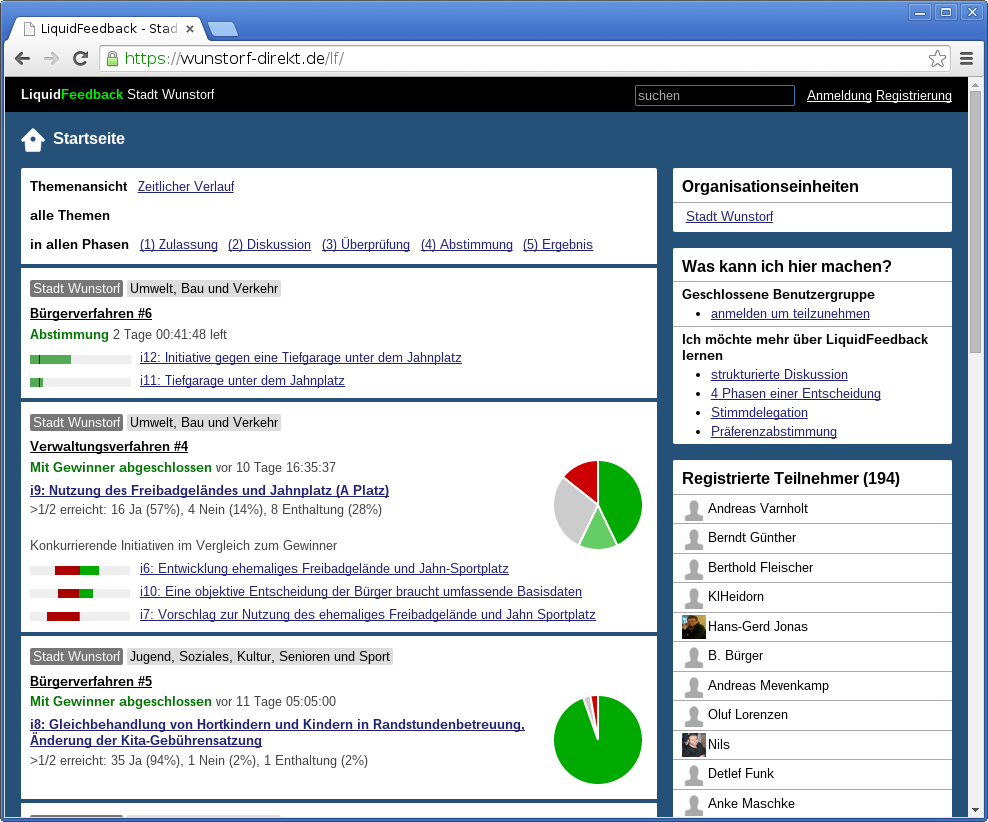

LiquidFeedback [LF] is an open source software for proposition development and decision making published by the Public Software Group e. V., Berlin, Germany [PSG]. [PLF, p.13] Since 2010 the software LiquidFeedback is used by political parties, non-governmental organizations, regional governments, and companies for opinion formation, binding decision making, and citizen petitions.

A revision control system is the standard way to track changes of the source code of a computer software developed by multiple authors. This technique is also used for many other purposes, like tracking changes to documents, books, datasets, product data, or any other kind of information. Different revision control systems are available on the market and used widely. Often used systems are Git [Git], Mercurial [Mercurial], and Subversion [Subversion]. Other software is incorporating aspects of revision control systems to track changes while providing other functionalities, e.g. Wiki systems like MediaWiki [MediaWiki] used by Wikipedia [Wikipedia].

But these systems lack support for collective decisions on incorporating changesets. In most implementations, either a user has write privileges or not. Therefore, in larger projects, especially projects with more than a few dozen active contributors, only a small number of people regularly have final control over the files held in the repository. They are moderating the process of applying changes and finally deciding if a change set will be included or not.

To overcome these limitations and to get rid of the need of privileged moderators, it is shown that it is possible to extend and use LiquidFeedback in such a way that the process of changing the files managed by a revision control system can be organized collectively by the members of the project team using LiquidFeedback's proposition development and decision making process. Furthermore, it will be shown that these concepts can also be adopted by many other systems which are utilizing revision control systems.

Through implementing a proof of concept, it is demonstrated that it is technically possible to organize democratic decision making on incorporating changes to files held in a repository. Therefore, the decision if a project makes use of privileged moderators or implements a democratic decision process is not a technical question anymore, but an organizational or political one. This opens new application fields for democratic processes in the context of revision control and at the same time new application fields for revision control systems in the context of democratic processes. It is also possible to create completely new application fields by using the synergistic effects created by utilizing LiquidFeedback with revision control systems.

As this paper addresses different scientific fields, the basic functionality of LiquidFeedback and revision control systems are explained in the following sections II and III.

II. Introduction to LiquidFeedback's Proposition Development and Decision Making Process

LiquidFeedback is an open source software, which can be installed on an internet server and used through a web browser. LiquidFeedback offers a unique proposition development and decision making process whose structure and main features are described in the following:

II.1. Organizational unit (short form: unit)

The units are the highest hierarchical structure of LiquidFeedback, intended to represent organizational units, like national, regional and local chapters. Units are organized as tree to organize subsidiary chapters below their superior chapters. Voting privileges are given to users per unit without inheritance to subsidiary or superior units. [PLF, p.158]

II.2. Subject area (short form: area)

Every unit has one or more subject areas, holding the possible issues together in groups of similar topics, e.g. finances, public relations, different fields of politics, etc. A subject area belongs to a unit. [PLF, section 4.8] [PLF, p.165]

II.3. Issue

An issue is a group of competing initiatives going together through the four phases of a decision in LiquidFeedback. An issue is automatically created when a new initiative is started and not placed into an existing issue. Each issue is identified by a unique number, which is automatically assigned when it is created. Per issue, not more than one initiative can be accepted as winner in the end. An issue belongs to a subject area. [PLF, section 4.4] [PLF, p.147] [PLF, section 4.8]

II.4. Initiative

The initiative is the main form to express a will in LiquidFeedback. It can consist of a proposal and/or reasons for it and/or reasons against other competing initiatives. Initiatives can be supported by users, changed until the verification phase begins, and finally be voted upon in the voting phase. An initiative belongs to an issue. [PLF, subsection 4.1.1] [PLF, section 4.4]

II.5. Draft

A draft is a version of an initiative. Every time an initiator changes the content of an initiative, a new draft is created. Old drafts are saved for future reference. [PLF, subsection 4.1.1]

II.6. Initiator

The initiator is the user who created an initiative. Only an initiator can change the content of an initiative during discussion. The initiator can invite other users as initiator, which gain the same rights as the original initiator after accepting the invitation. This includes the right to grant or revoke initiator privileges to/from another initiator of the same initiative. [PLF, subsection 4.1.1] [PLF, p.154]

II.7. Supporter

A supporter is a user supporting an initiative, helping it to fulfill the quora measured at the end of the admission and verification phases. Users which have rated a suggestion as “must” but “not fulfilled”, or “must not” but “fulfilled” are counted as potential supporters, supporting the initiative only under the requirements expressed in the rated suggestions. [PLF, (sub)sections 4.1.1, 4.1.2, 4.3, 4.6]

II.8. Suggestion

Suggestions are placed by users to propose improvements for initiatives. This can range from a simple typo or grammar correction to complex changes of the initiative. All supporters of an initiative can rate suggestions to let the initiator(s) know about the collective opinion and how they could improve the initiative. Suggestions can be rated as “must”, “should”, “should not”, “must not” and whether they are “implemented” or “not implemented”.

If a suggestion will be implemented or not is the decision of the initiator(s) only. But if a widely demanded suggestion is not implemented in the initiative, any user can start an alternative competing initiative implementing this suggestion (similar to “forking” a software project). [PLF, subsection 4.1.2]

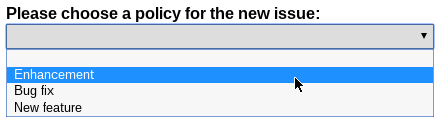

II.9. Policy (rules of procedure)

A policy (also referred to as “rules of procedure”) is a set of configuration settings, including:

- how long the four phases of a decision should last,

- which quora are applied at the end of the admission and verification phases, and

- which majorities are needed in the voting phase to become accepted as winner.

The initiator of an initiative, which is not placed in an existing issue, can choose the policy to use for the newly created issue. As there is no computable way to check if the correct policy is chosen, it is up to the users not to support issues which are misusing policies. [PLF, subsection 4.7]

II.10. Predictable timing of four phases

An issue in LiquidFeedback is going through four phases: [PLF, section 4.6]

- admission phase,

- discussion phase,

- verification phase, and

- voting phase.

The duration of the four phases depends on the settings of the chosen policy. Therefore the timing can be predicted. [PLF, section 4.5]

II.11. Using quora to moderate the process

To moderate the overall process and to filter out issues and initiatives which do not have enough support, a quorum needs to be passed after the admission phase and before the voting phase. How many supporters are needed to let an issue or initiative pass is configured in the chosen policy. [PLF, section 4.3] [PLF, section 4.7]

II.12. Transitive delegated voting (Liquid Democracy)

The basic idea of Liquid Democracy is a democratic system in which issues are decided by direct referendum, but votes can be dynamically delegated by topic as not every participant has time and personal knowledge about every issue. Implementing this idea allows also to dynamically find experts for specific subject areas and issues in a democratic and traceable way. Other terms referring to the same idea are “Delegated Voting” and “Proxy Voting”. [PLF, chapter 2]

II.13. Minority Protection with the Harmonic Weighting algorithm for a fair share of display space

Even though any democratic decision that has at least one dissentient vote leads to a overruled minority, it is still possible to protect minorities in democratic processes. The most important measures of protecting minorities are unalienable, constitutional rights, which are granted in most democracies. But this cannot be ensured algorithmically and is therefore out of scope of computer software. [PLF, section 4.10]

Another form of minority protection is to give minorities a fair chance to promote their positions for discussion in the democratic process. [PLF, section 4.10]

LiquidFeedback implements this form of minority protection: minorities are given the right to promote their positions. Technically there is no limit in the number of issues to be discussed in an online system since many issues can be handled simultaneously (unlike “offline” conventions, where usually only one issue can be discussed at a time). But there is another limit of online systems: the display is limited and can only present a small amount of information at the same time and users can only absorb a limited amount of information per time. To ensure a fair share of this limited display space, LiquidFeedback implements the Harmonic Weighting algorithm, which proportionally shares the available display space between all initiatives in such a way that minorities can put their issues and initiatives into the debate while noisy minorities (e.g. so-called internet trolls) are not able to harm other minorities by allocating an unfair share of display space by placing a large amount of initiatives. [PLF, section 4.10] [Evolution]

II.14. Preferential voting avoiding tactical behavior

LiquidFeedback utilizes a modern preferential voting system for the final decision in the voting phase of an issue which is based on the Schulze Method (sometimes referred to as Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping). The Schulze Method fulfills certain criteria which are desired for democratic processes, e.g. [Schulze] [PLF, section 4.14]

- Independence of Clones,

- Monotonicity,

- Schwartz Criterion, and

- Independence of Smith-dominated Alternatives (ISDA or Smith-IIA).

While fulfilling several further properties, the Schulze Method is implemented in LiquidFeedback with a robust tie breaking system, solving situations the Schulze Method cannot solve alone. [Schulze] [TieBreaker] The most notable property of the Schulze Method is to lessen incentives for tactical voting behavior. [PLF, section 4.14]

II.15. Further process and implementation details

The LiquidFeedback proposition development and decision making process and it's implementation in LiquidFeedback Core [Core] and LiquidFeedback Frontend [Frontend] utilize further concepts to provide a scalable way of collective proposition development and decision making and is actively advanced regarding theory and practice by the Public Software Group e. V. [PSG] and Interaktive Demokratie e. V. [IAD], both in Berlin, Germany. [LF] [PLF] [LDJournal] [liquidfeedback.org]

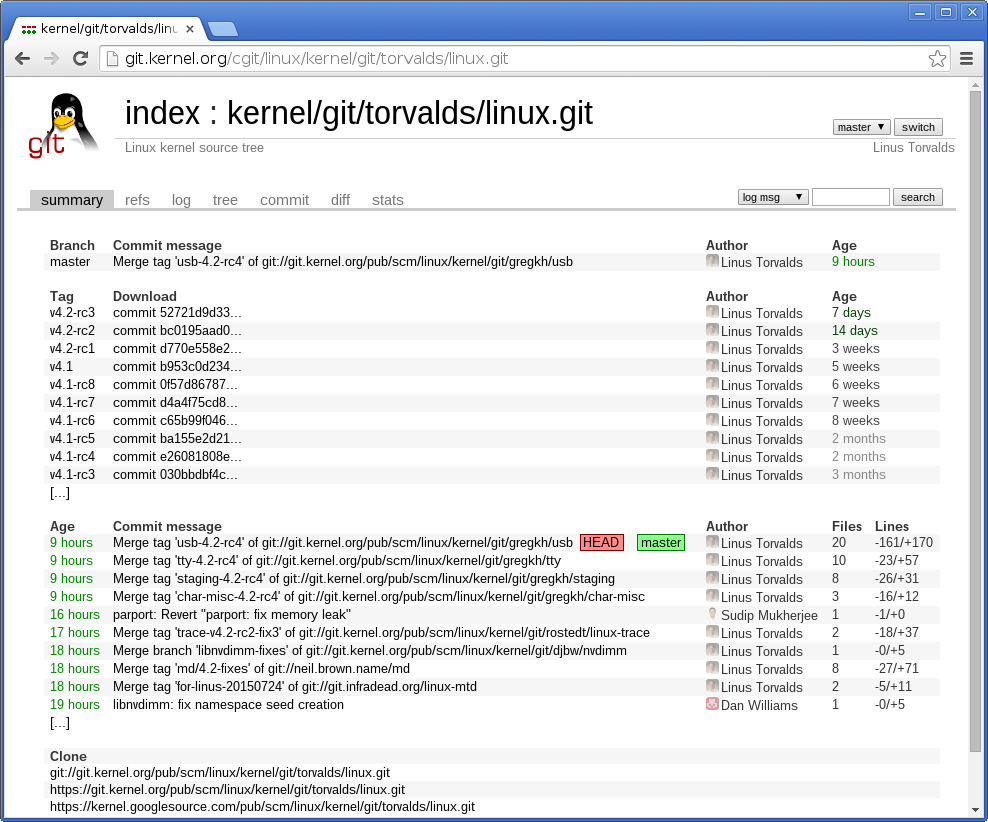

III. Introduction to Revision Control Systems

A revision control system is a computer software to manage different versions of data files. Especially it is used to track changes on text files like source code, configuration files, documentation, articles, books, but also to track changes on product data, i.e. construction data for cars, airplanes and other products.

With a revision control system, so-called “repositories” can be created, which hold different versions of files and track their changes. A bundle of changes to files in the repository is often called changeset. An important feature of revision control systems beneath the tracking of changes is the ability to go back to any past revision of a file or any previous changeset, as long as it is stored in the repository.

Nowadays revision control systems use the internet to allow groups of creators working together from different places of the world while tracking each changeset back to its originator. This enables groups of creators to collectively work on source code, articles, or other data while minimizing communication overhead.

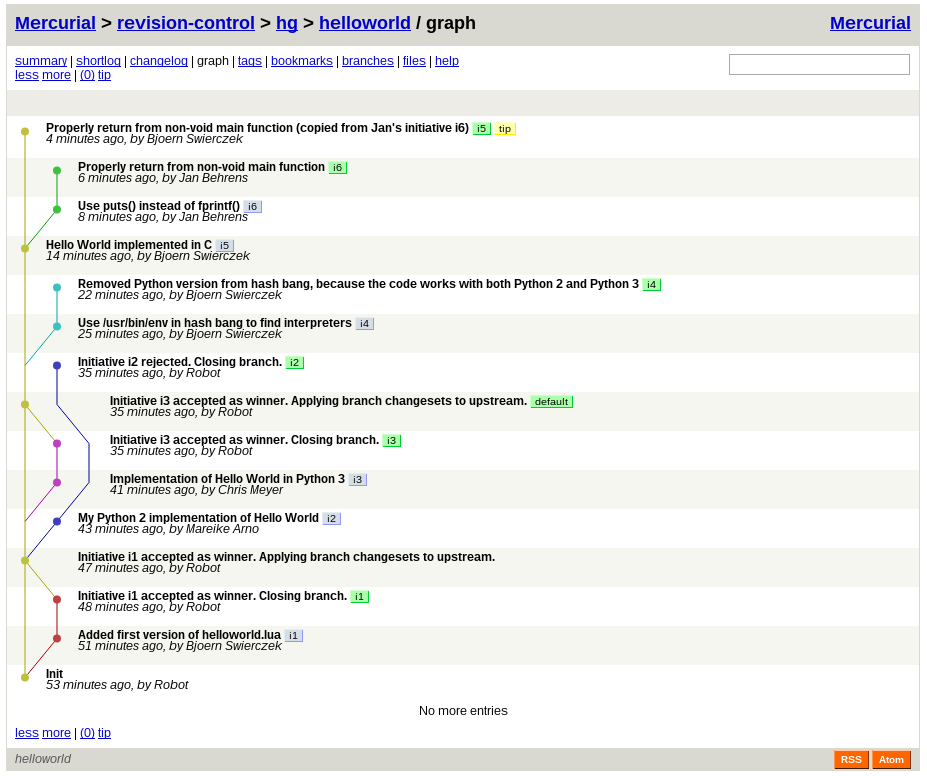

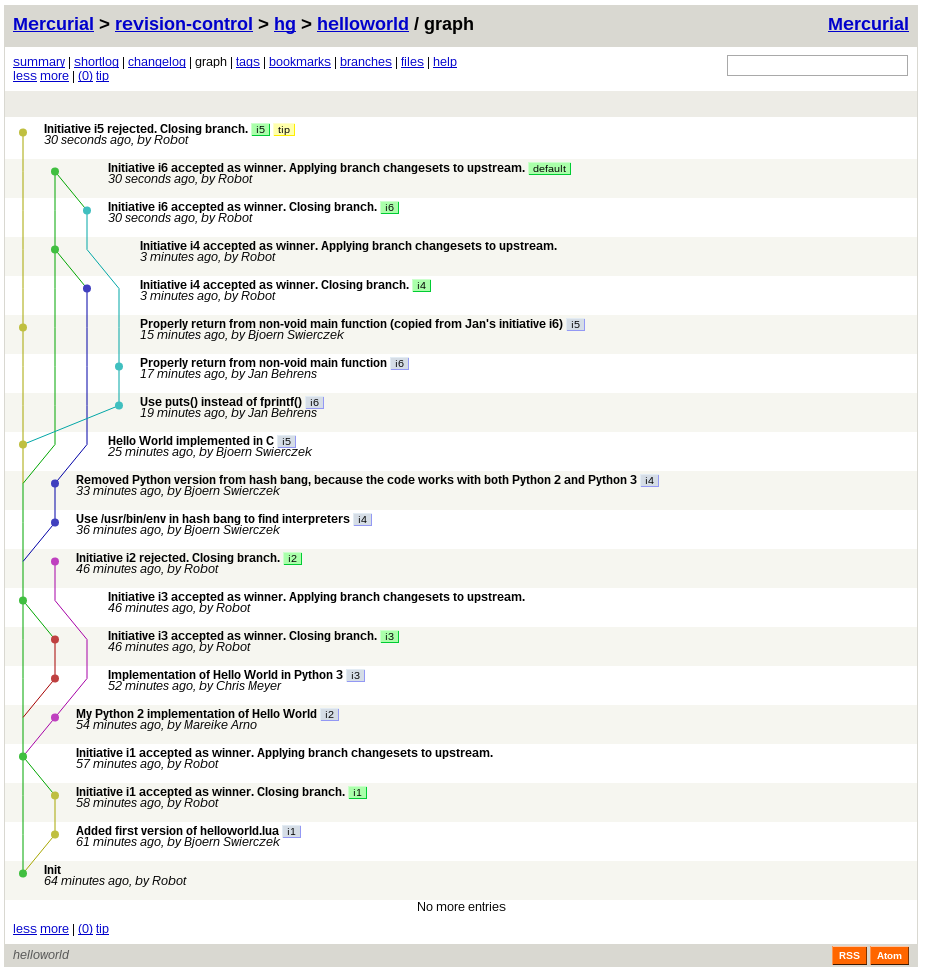

Most revision control systems are offering the possibility to create “branches”, i.e. giving a name to a series of changesets which are not (yet) part of the official main branch. The official or main branch of a project is often referred to as trunk or master branch.

To incorporate changesets made in branches into the trunk or master branch, most revision control systems have a merge command, which allows merging changes.

Aspects of revision control systems are also incorporated in other computer software for tracking changes, e.g. in Wiki systems like MediaWiki used by the Wikipedia. [MediaWiki] [Wikipedia]

IV. Extending LiquidFeedback for use with a revision control system

In this section, it is shown how LiquidFeedback can be extended to collectively decide on merging changesets to the trunk or master branch of a repository.

IV.1. Terms

The terms used by LiquidFeedback are created for generic democratic decisions. For using the LiquidFeedback process in the context of revision control systems, I propose a mapping of the terms as follows:

Unit → RepositoryArea → Module

Issue → Issue

Initiative → Branch

Draft → Changeset

Suggestion → Suggestion

IV.2. The basic idea

The basic idea is that changes to the files held in the trunk of a repository require a formal decision by the project team (or another empowered group of persons) using the LiquidFeedback proposition development and decision making process.

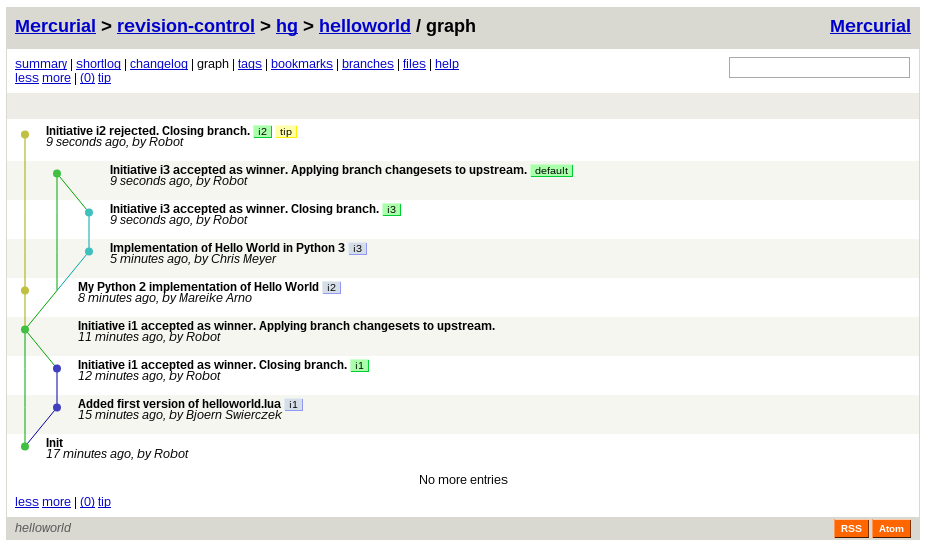

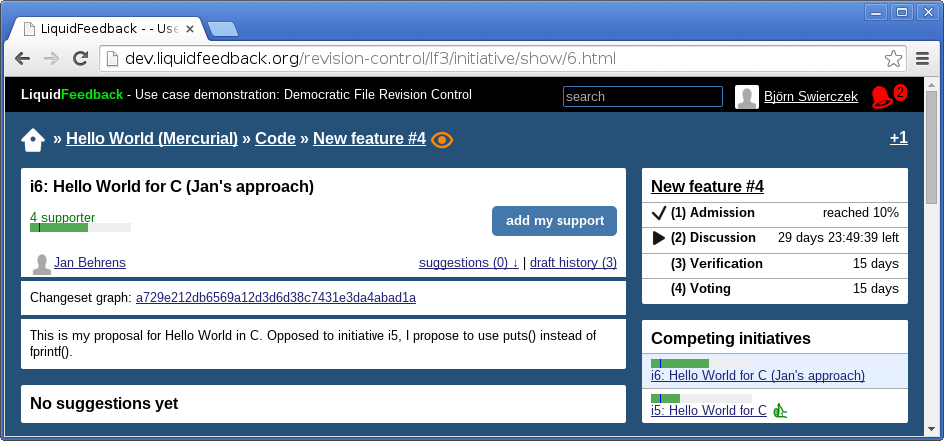

To achieve this functionality, it is proposed to extend LiquidFeedback in such a way that each initiative represents a branch in the repository and each draft represents a changeset of this branch. Even while I suggest to map “initiatives” to “branches” for this specific purpose, in fact they will still be LiquidFeedback initiatives, which need to go successfully through all four phases of the LiquidFeedback proposition development and decision making process to become accepted.

During these phases, the members of the project team (or other empowered persons) can use all regular functionalities of LiquidFeedback to debate and decide about the branch. At the same time, all regular functionalities of the revision control system can be used with one exception: branches with names possibly referencing an LiquidFeedback initiative (i.e. having a name in a certain format, e.g. “i123” to reference the initiative with the ID 123) can only be committed to the repository if an initiative with the referenced ID exists and is still in admission or discussion phase. Furthermore the user committing the branch needs to be initiator of that initiative. This also allows to merge changesets created in other branches to one's own branch, i.e. one's own initiative.

To enhance a branch, suggestions can be made unless the verification phase has already begun. The suggestion may include additional changesets to be added by the initiator(s) if they like to incorporate them into their branch.

Any member of the project team (or other empowered persons) can also create a competing branch by creating an alternative LiquidFeedback initiative in the same issue unless the voting phase has already begun.

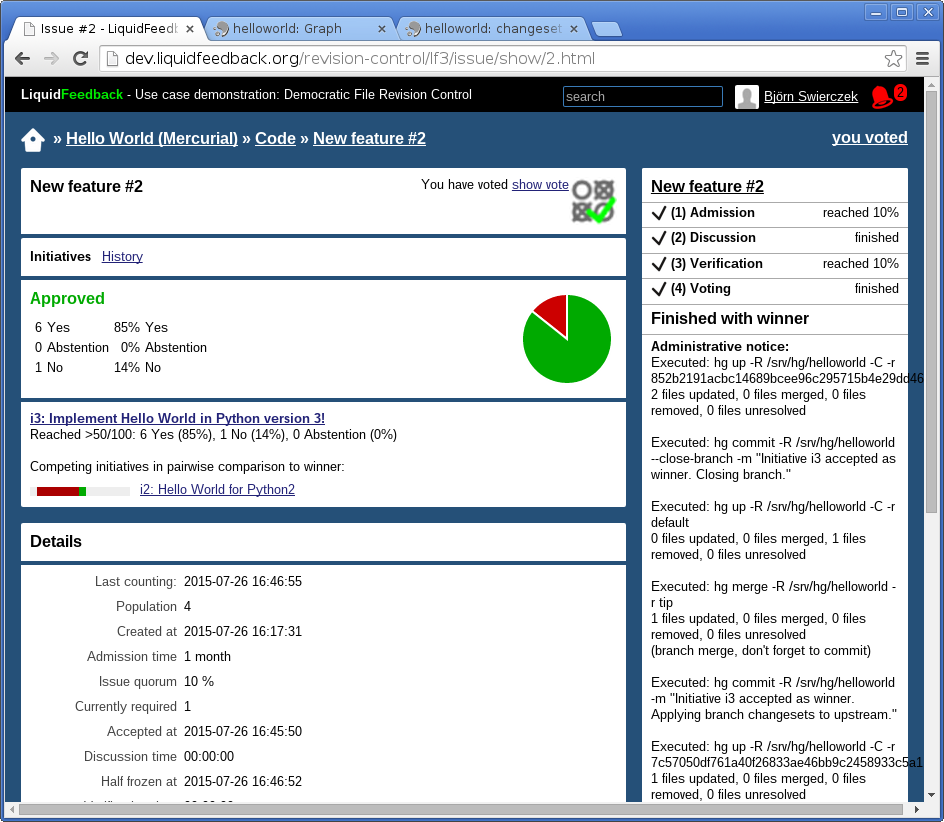

After the voting phase of an issue ends, it is proposed to merge that branch to the project's trunk which has been declared winner of the issue, if any.

The policies (rules of procedure) framework of LiquidFeedback can be used to allow different quora, timings and majorities for different types of branches, i.e. for bug fixes, enhancements, documentation, etc. to reflect the different needs of different types of decisions.

IV.3. Concurrency of decisions

A special problem seems to be the fact that other changesets may have been already applied to the trunk or master branch between proposing a changeset the first time and the decision after the four phases of LiquidFeedback. Using different timings, it is also possible that a changeset is applied before another changeset although it has been started after the other changeset's LiquidFeedback initiative already reached the verification or voting phase. Therefore, it is not possible to reflect changes made by the “faster” changeset anymore. This can lead to a merge conflict, i.e. two changesets changing the same part of a file. Thus a proposed changeset can break at any time, so it would not be possible to apply the changeset at the current time.

But more important would be the answer to the question: “Would the changeset still apply without merge conflicts after its decision and after other changesets are applied to the trunk or master branch?”

IV.3.a. Predict future changesets

We cannot predict which changesets will be accepted in the end. But at any time we could make useful assumptions based on the approval rates (supporter counts) made during the first three phases of LiquidFeedback. It could be assumed that any branch which has been accepted for discussion and has an approval rate of more than 50% (and being the initiative with the highest supporter count in its issue) will be accepted as winner later. Based on this assumption, we can try to apply the associated changesets in the order of the predictable end of the voting phase and check if they cleanly apply. If any changeset would not be (hypothetically) applicable anymore, the initiators or interested users could be informed appropriately.

This prediction system could be extended to a more sophisticated system, which traces different paths in parallel.

IV.3.b. Exclusions and requirements

Another mechanism to solve the problem of concurrent decisions could work as follows: LiquidFeedback could be extended to allow the initiator(s) to add two lists of references to other branches, which are expected to be decided previously. An entry in one list indicates that the current branch should *not* be applied if at least one of the referenced branches is accepted (exclusion) while all branches referenced in the other list need to be accepted (requirement).

As soon as an excluded branch is accepted or a required branch is declined, the branch should become automatically revoked unless the initiative is still in admission or discussion phase and the initiator(s) could still make appropriate changes healing the branch. For the purpose of automatic revocation, a new finished state for LiquidFeedback issues could be introduced: “Canceled because of unfulfilled precondition”.

This system could be extended by a more sophisticated way to describe the preconditions, i.e. nested sets of exclusions and requirements combined with logical “AND”/“OR” operations.

IV.3.c. Let the users decide

A very easy way to solve problems related to concurrency is to simply ignore merge conflicts algorithmically but let the users handle them. For example, after the changesets associated with a LiquidFeedback initiative cannot be merged due to conflicting changesets, any user could start another initiative and post a changeset which fixes this conflict. As soon as this initiative is accepted as winner, this fixing changeset will be incorporated together with the changesets of the initiative which couldn't be merged previously. For this purpose, a special policy with an appropriately short discussion and decision time could be configured in LiquidFeedback.

IV.3.d. Merging 2nd winner if 1st winner fails

In situations where changesets associated with a LiquidFeedback initiative which has been declared winner cannot be merged due to other conflicting changesets which already have been merged, one could come up with the idea to try merging the 2nd winner (or the 3rd if the 2nd fails too, and so on), based on the motto “you had your chance”. But this would not be wise, as it could create an unwanted feedback to the behavior of users. A user who is obsessed about an initiative could try to create short lasting initiatives (e.g. with a bug fix or documentation policy), or modify already running initiatives, to intentionally break a promising initiative. This attempt could be easily hidden, e.g. as typo fix or an enhancement of documentation. If such an attempt is successful, a situation could arise where an initiative being the first winner is not applicable anymore, but the second one (the one the user is obsessed about) is. As this would be unfair, only first winners should be merged.

IV.4. Accreditation of users

Any democratic decision making system needs a proper accreditation to ensure that every eligible person (e.g. developers of a software project) get exactly one account (and therefore one vote) and nobody else. This condition is also valid for LiquidFeedback and therefore also for using LiquidFeedback with revision control systems. [PLF, subsection 6.1.1]

IV.5. Verifiability by the users

Democratic decisions need to be verifiable. It is impossible to make electronic votings secret and at the same time verifiable by the participants. Therefore, the only way to implement electronic decisions verifiable by the participants are open recorded votes. [PLF, chapter 3]

V. Technical Implementation

V.1. Environment

To use LiquidFeedback and one or more revision control systems on an internet server, it is necessary to setup the following open source software packages according to the setup instructions provided by the distribution and package maintainers:

- Linux or BSD (operating system) [Debian] [ArchLinux] [FreeBSD],

- HTTP web server supporting the CGI interface [Apache] [Lighttpd],

- PostgreSQL (database server), version 9.1 (or higher) [PostgreSQL],

- LiquidFeedback Core, version 3.0.5 [Core],

- Lua (programming language), version 5.2 or 5.3 [Lua],

- Moonbridge Network Application Server for Lua, version 1.0.1 [Moonbrige],

- WebMCP (web application framework), version 2.0.2 [WebMCP],

- Markdown2 [Markdown2],

- LiquidFeedback Frontend, version 3.0.9 [Frontend],

- one or more revision control systems, e.g.

- Git (distributed version control system) [Git], including

- Gitweb [GitWeb] and

- git-http-backend [git-http-backend],

- Mercurial (distributed source control management system) [Mercurial], including

- HgWeb [HgWeb],

- other revision control systems.

- Git (distributed version control system) [Git], including

V.2. Configuring the HTTP web server to authenticate users against LiquidFeedback

The web server needs to be set up in such a way that users need to log in with a user name and password (via HTTP access control). To allow authentication with the username and password used in LiquidFeedback (single sign-on, SSO), a htaccess file as used by many HTTP web servers to store user authentication data can be created using the following shell command, which should be run regularly to reflect changes of the LiquidFeedback user database in the web server's authentication file (<name of LiquidFeedback database> needs to be replaced by the name of the LiquidFeedback database in PostgreSQL):

echo "SELECT login || ':' || password FROM member WHERE NOT locked;" | psql <name of LiquidFeedback database> -A -t > /etc/lighttpd/htpasswd.new && mv /etc/lighttpd/htpasswd.new /etc/lighttpd/htpasswd

V.3. Configuration of LiquidFeedback

V.3.a. Setup for controlling revision control systems

For LiquidFeedback, I assume the following setup:

- The LiquidFeedback web service provided by LiquidFeedback Frontend is available at: http://liquidfeedback/lf3

- The accreditation of the team members (or other empowered persons) as LiquidFeedback members is finished and done properly. [PLF, subsection 6.1.1]

V.3.b. Setup for a project

For any project, a unit needs to be created in the administration interface of LiquidFeedback Frontend. The revision control system and the repository used by this project need to be configured in the external reference field of the unit created. The format of the configuration is

<repository type> <path on file system> <web url of repository>

V.4. LiquidFeedback Extension for Revision Control Systems (lf4rcs)

To allow LiquidFeedback (and therefore its users by democratic decision) to actually control one or multiple revision control systems, I implemented an extension for LiquidFeedback. This extension implements a modular framework which can be configured to be used with revision control systems. The extension consists of three parts:

- controlling and tracking commits to a repository,

- handling finished issues and winner initiatives, and

- formatting of web links to changesets.

The following source code needs to be loaded by the configuration of LiquidFeedback Frontend:

It is necessary to create /srv/commithook.lua with the following content:

… and to make it executable by the operating system:

chmod +x /srv/commithook.lua

V.5. Configuration for controlling Git

V.5.a. Setup for revision control by decisions made in LiquidFeedback

The following configuration is assumed for the project specific setup in the following subsection b:

- The root of the repositories is /srv/http/git

- The repository directories are owned by the web server operating system user

- The repository directories can be read and written by web server operating system user

- The directory /srv/git can be read and written by web server operating system user

- git-http-backend is serving repositories at the base address http://liquidfeedback/git/

- Gitweb is serving repositories at the base address http://liquidfeedback/gitweb/

The following source code needs to be loaded by the configuration of LiquidFeedback Frontend after lf4rcs has been loaded:

V.5.b. Setup for a project

For any project, a bare git repository needs to be created:

git init --bare /srv/http/git/helloworld.git

A call of the lf4rcs commit hook needs to be added to the hooks of the git repository (assuming the corresponding LiquidFeedback unit ID is 1):

Finally a clone of the repository has to be created:

cd /srv/git/

git clone /srv/http/git/helloworld.git

The configuration stored as external reference of the corresponding LiquidFeedback unit needs to be set to:

git /srv/git/helloworld http://liquidfeedback/gitweb/helloworld.git

V.6. Configuration for controlling Mercurial

V.6.a. Setup for revision control by decisions made in LiquidFeedback

The following configuration is assumed for the project specific setup of the following subsection b:

- The root of the repositories is /srv/hg

- The repository directories are owned by the web server operating system user

- The repository directories can be read and written by web server operating system user

- HgWeb is serving repositories at the base address http://liquidfeedback/hgweb/

The following source code needs to be loaded by the configuration of LiquidFeedback Frontend after lf4rcs has been loaded:

V.6.b. Setup for a project

For any project, a mercurial repository needs to be created:

hg init /srv/hg/helloworld

A call of the lf4rcs commit hook needs to be added to the hooks of the Mercurial repository (assuming the corresponding LiquidFeedback unit ID is 2):

The configuration stored as external reference of the corresponding LiquidFeedback unit needs to be set to:

hg /srv/hg/helloworld http://liquidfeedback/hgweb/helloworld

V.7. Configuration for controlling other revision control systems

An implementation for any other revision control system can be carried out similarly to the previously described setup using Git and/or Mercurial, as long as the revision control system supports:

- named branches,

- a merge facility,

- and a hook which allows external control over commits to a repository.

V.8. Using the system

It is assumed, that the users of the repository have already checked out a local copy of the repository.

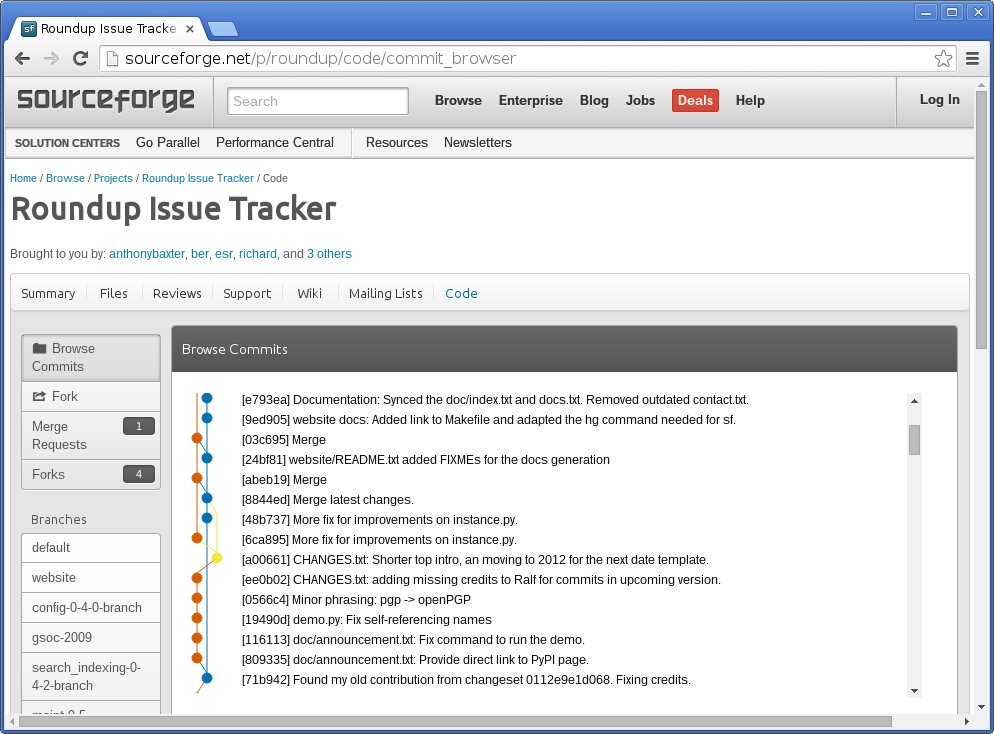

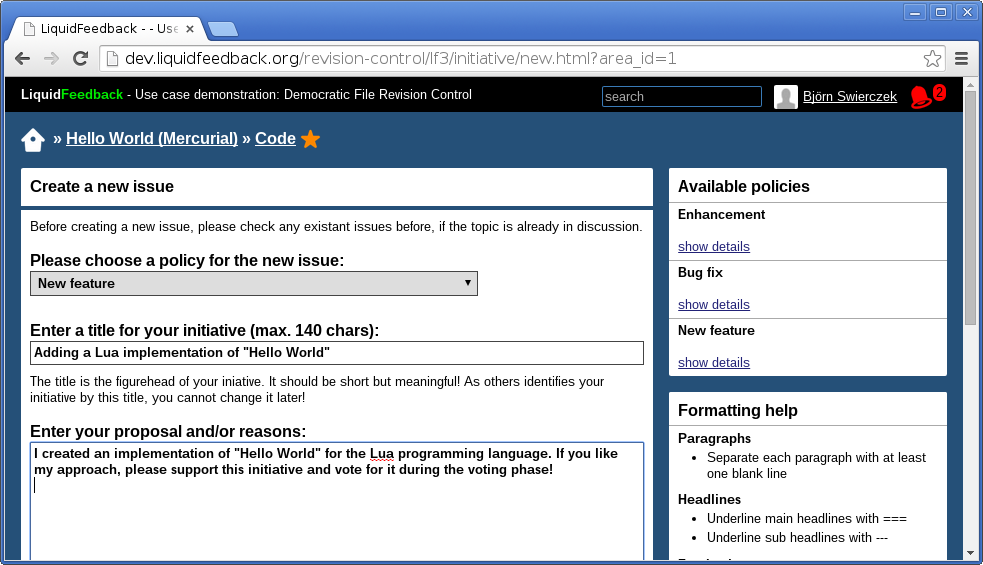

V.8.a. Creating an initiative in LiquidFeedback

To commit changesets to a repository controlled by LiquidFeedback as described before, a user must first create an initiative in the unit corresponding to the repository:

- open the appropriate area in the LiquidFeedback unit corresponding to the repository for which the changeset is intended,

- start a new initiative,

- enter a meaningful title for the changes,

- enter a draft describing the changes and reasoning them,

- actually create the initiative by publishing it.

V.8.b. Committing changesets

To associate changesets to the initiative created in LiquidFeedback, a user must mark them appropriately with a branch name in the following format, where <ID of initiative> is to be replaced with the numeric ID of the initiative:

i<ID of initiative>

As long as this initiative is in admission or discussion phase and the user is still initiator of the initiative, the user is allowed to push further changesets for this branch.

V.8.c. Committing changesets using Git

The user needs to mark the leading head of the changesets to be associated with the LiquidFeedback initiative as Git branch with the corresponding name, e.g. i123 for the initiative with the ID 123.

git branch i123

git checkout i123

The user can switch to different branches (associated with different LiquidFeedback initiatives):

git checkout i78

The user may push changes to the server repository, as long as all initiatives affected by the push request are still in admission or discussion phase:

git push origin

V.8.d. Committing changesets using Mercurial

The user needs to mark all changesets to be associated with the LiquidFeedback initiative as Mercurial branch with the corresponding name, e.g. i123 for the initiative with the ID 123.

hg branch i123

The user can switch to different branches (associated with different LiquidFeedback initiatives):

hg up i78

The user may push changes to the server repository, as long as all initiatives affected by the push request are still in admission or discussion phase:

hg push --new-branch

V.8.e. Committing changesets using other revision control systems

For other revision control systems, the features corresponding to the features described for Git and Mercurial above should be used to accomplish these tasks.

V.8.f. Providing links to changesets associated with an initiative

For any LiquidFeedback initiative which has associated changesets, links to the corresponding views of the revision control system's frontend will be provided in LiquidFeedback to allow direct access by the user.

V.8.g. Commit changesets associated with winning initiatives

As soon as an initiative has been declared as winner by LiquidFeedback, the corresponding changesets will be applied automatically to the trunk or master branch of the repository if it is applicable without merge conflicts.

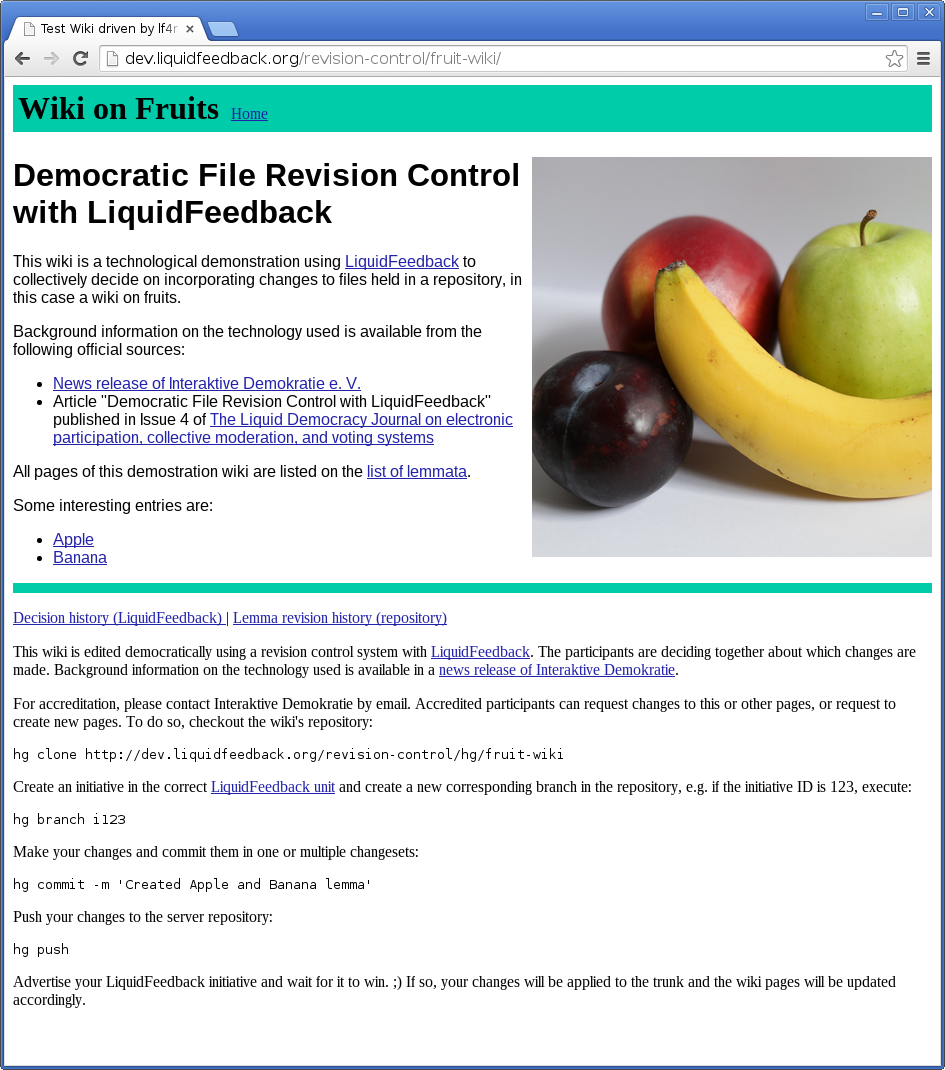

V.9. A cherry on top: adding Wiki functionality

It is possible to build a Wiki functionality on top of the setup described in the previous subsections. To demonstrate this, a repository may hold a file per Wiki page containing the content of this page (formatted with Markdown2). The following source code can then be run after each merge of a branch with the trunk or master branch of the repository:

Furthermore, a HTML template file needs to be placed in the root of the repository. In this file, the place to put the rendered content of each page has to be marked with the string “$content$” in a separate line:

The source code of the Wiki engine must be executed as follows, assuming it is placed in the directory /srv/ (<repository path> has to be replaced by the path to the repository containing the Markdown2 formatted files while <target path> needs to be replaced by a path to store the created HTML pages, which could be served by an HTTP web server):

/srv/wikify.lua <repository path> <target path>

Unusual for a Wiki, editing of pages is carried out by editing files and committing the changesets to a repository. But this approach is only a proof of concept and could be extended to create an integrated (democratic) Wiki user interface. It would also be possible to use other parser engines to support different types of formatting languages. Even the integration of a comfortable WYSIWYG text editor is thinkable.

VI. Conclusion

VI.1. Democratic file revision control is possible

Revision control of files held in a repository can be done collectively in a democratic way. An approach to extend the already existing software LiquidFeedback to utilize its unique proposition development and decision making process for that purpose has been shown.

VI.1.a. Eliminate privileged moderators

The described approach can be used to get rid of the need of privileged persons moderating the process of incorporating changes and controlling the write-access to the repository.

VI.1.b. Increase decision quality by finding specialists for decisions

Instead, the idea of Liquid Democracy can be used to dynamically delegate votes based on subject areas and issues to find experts which are specialists for these subject areas or issues and able to make decisions with a higher quality than the average user would be able to.

VI.1.c. Potential of quality increase

The described approach has the potential to drastically increase the quality of incorporated changesets to files created collectively by larger groups. Therefore, projects making use of the described approach could increase their overall output quality.

VI.2. Affected fields

Any use of revision control systems to coordinate the work of multiple persons (e.g. authors) is from a technical point of view exactly the same. It is controlling versions and tracking changes of files held in a repository. Therefore, it can be deduced that the mechanisms shown in this paper are applicable to any possible use case of revision control systems.

VI.2.a. Application fields already using revision control systems

Revision control systems are used e.g. for

- software development,

- configuration management,

- article, book, etc. writing,

- construction and engineering,

- scientific purposes,

- business purposes,

- art and design, and

- media.

This incomplete list of actual use cases of revision control systems shows that the described approach opens a very wide range of new application fields of LiquidFeedback and its proposition development and decision making process.

VI.2.b. Applications in democratic context

At the same time, new application fields for revision control systems are opened in contexts which did not allow use of such systems before, because the final control needs to be executed democratically.

VI.2.c. New application fields created by synergistic effects

It is possible to create complete new application fields, based on the synergistic effects of using LiquidFeedback's proposition development and decision making process to control revisions of files in a repository.

It has already been proposed to use revision control systems in the context of tracking governmental resources. [Simmons]

VI.2.d. Applications integrating aspects of revision control, e.g. Wiki, MediaWiki and Wikipedia

There are more application fields where aspects of revision control systems are integrated in software systems while normal users are sometimes not even aware of it.

Famous examples are the hundreds of existing Wiki systems, most famously the MediaWiki used by the Wikipedia, which is edited by thousands of authors. Such systems are using a revision control system to track changesets and the current version of the documents presented by the Wiki system.

But in conflict situations, edit wars may arise and then the platform administrators need to “lock down” the article and review all changes manually and decide about them eventually. To get rid of this problem, the described approach can also be adopted by Wikis, allowing them to organize their internal processes in a more democratic way.

Therefore, the described approach is also a prototype, how infrastructure platforms like the Wikipedia could be further democratized.

VI.3. Prospects

VI.3.a. Further extending the approach

The presented approach will be incorporated into the official software package of LiquidFeedback Frontend [Frontend], which is maintained by the Public Software Group [PSG]. It is possible to further extend this approach by using LiquidFeedback for a more fine-graded control of a repository, e.g. to limit changesets to certain modules, directory and/or file name patterns, or other applicable criteria depending on the area and/or the policy chosen for the issue. It is also thinkable to associate changesets with suggestions. Furthermore, it is possible to integrate a complete visualization of the information and meta information held by repositories in LiquidFeedback. Deeper integration can be achieved by allowing modification of the files of a repository branch directly in LiquidFeedback (e.g. integrating a WYSIWYG text editor or other file editors) and automatically generate changesets representing the changes made to the files and associate them with LiquidFeedback initiatives. Combining this with a sophisticated Wiki engine rendering the files held in the trunk or master branch of a repository would provide a fully integrated and complete democratic development and publishing platform for generic use in different fields of application.

VI.3.b. Meta level

On the meta level, this paper also shows that LiquidFeedback's proposition development and decision making process is not limited to conventional democratic decisions in parties and other organizations, but it can also be adopted to completely different application fields. This should endorse examination of other electronic systems, which are used by a larger group of people, regarding how to take advantage of LiquidFeedback's proposition development and decision making process.

VI.3.c. Social impact

As with any technological change, the broader use of LiquidFeedback in the context of revision control and other application fields has to go along with a cultural adoption of the new technology. The presented approach allows to collectively organize any type of data related work which is carried out by a larger group of people without the need of a moderator or a decision hierarchy. Companies, organizations, and voluntary projects can rethink their organizational scheme to master the challenges of the digital revolution, to set free the wisdom and abilities of their workers, and to benefit from reduced overhead. Therefore, the details of application in different fields and the consequences for companies and organizational structures but also for the working people needs further research and discussion in different scientific fields.